Technical Update on Photon

Background

The majority of this post is from an old document that has never been released. Before starting, I would like to talk a bit more about why the first version of Photon renderer is not developed anymore.

Initially, it was a side project where I experiment with some global illumination techniques for my game engine (called Tokzin), and both of them were written in Java. It had occurred to me that Java, although easy to code and sometimes outperforms compiled languages1 thanks to its JIT system, the restricted accessibilities to system memory makes it hard to implement some of the low level optimizations. In 2016, I decided to rewrite the rendering engine in C++ for better performance, and ported most of the code from the original Java codebase. It is worth noting that the C++ version was more than 20% faster rendering the Crytek Sponza2 scene than its Java counterpart out of the box. At that time, I bumped Photon’s version number into 2.0 and has been adding features here and there since then.

Main Interface

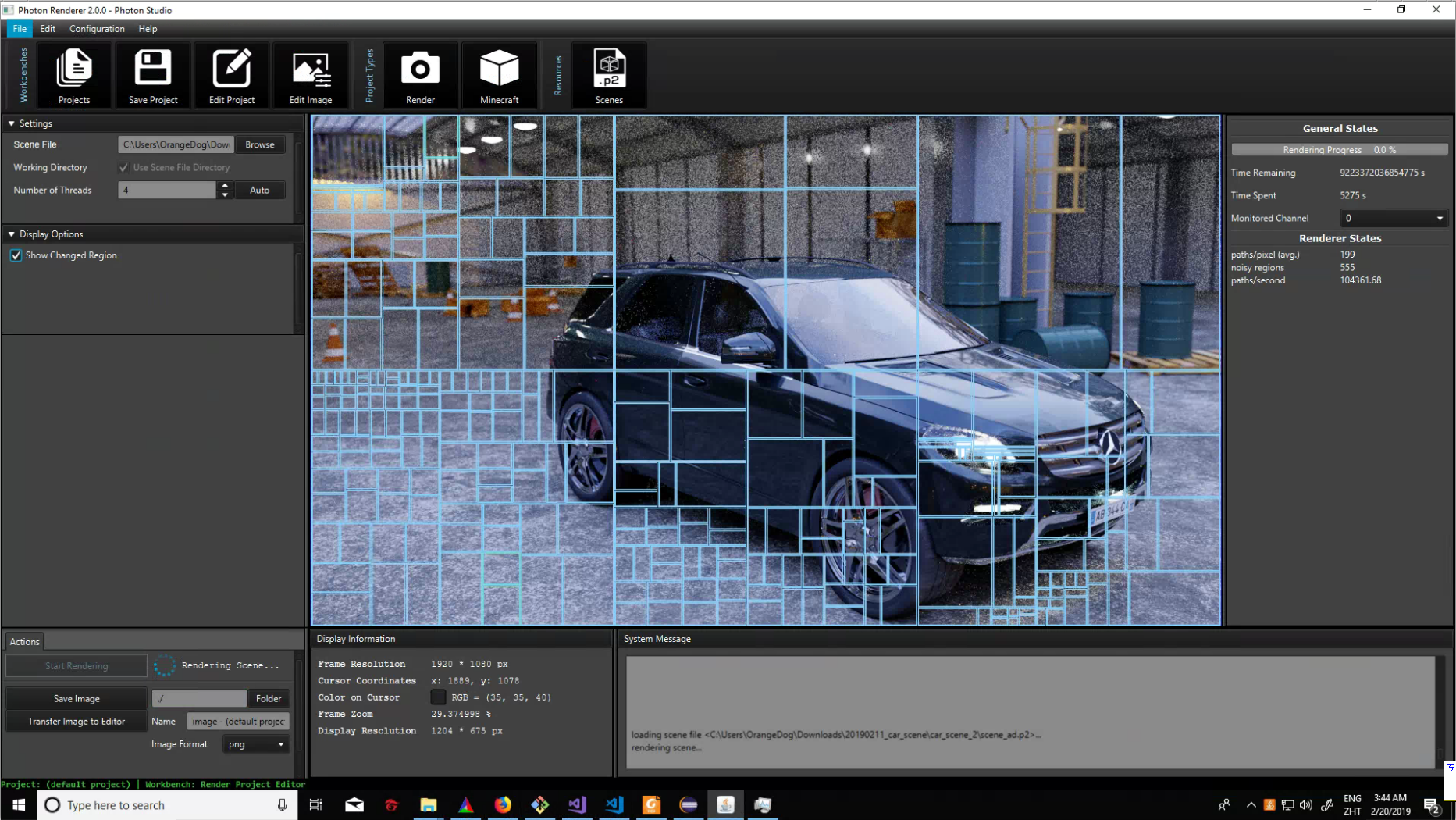

Photon is written with C++17 and provides a C API for other applications. It also comes with a CLI and a JavaFX based GUI capable of rendering static images as well as image sequences (CLI only). Another unique aspect of Photon is its scene description language (photon scene description language, PSDL), as it is not only a data-storing medium but also a command-line system, which means it is possible to create procedurally generated assets in PSDL entirely. A Blender add-on is also provided for ease of content creation, such as modeling a scene and export it as PSDL for rendering. Below is an image of the JavaFX GUI in action:

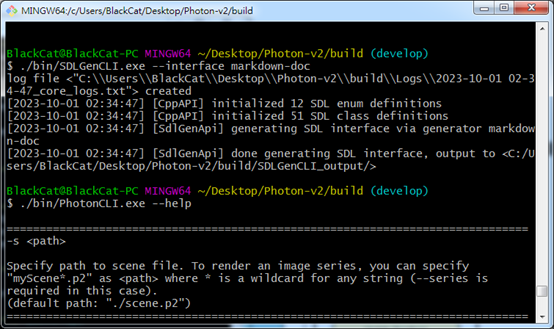

Photon-v2 comes with an application called PhotonCLI, which is a command-line interface of the render engine. Command-line interface can come in handy if you are batch rendering or using it on a remote server. It also, in theory, offers slightly better performance in terms of render time.

Dataflow

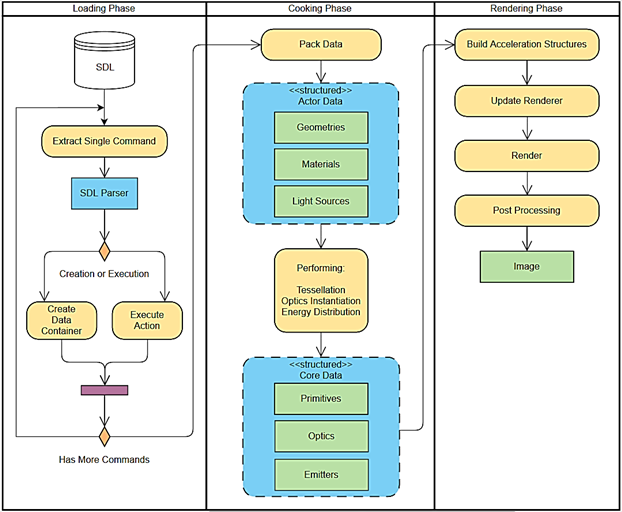

A program is essentially a function mapping input and output data. When a user feed a program with some input data, it will be transformed by a series of components in the program, much like an assembly line, and the output data is obtained as a product in the end. To understand its architecture and design principals, the best way is to have a clear picture of its dataflow in my opinion. Shown below is a vastly simplified version of the dataflow within Photon renderer:

As you can see, the dataflow can be divided into 3 phases: loading, cooking, and rendering. In the loading phase, SDL is being parsed command after command, and each command can either create a data container or perform actions. Data containers are named resources, thus each command is not an independent unit and can reference each other where applicable. In the end of the phase, data containers such as geometries, materials and light sources are extracted from the SDL and is ready for entering the next processing phase.

The next stop for data processing has a rather interesting name, cooking3 phase, as I consider the data from previous phase is “raw”. The purpose of cooking is to turn raw data into something that is suitable for rendering. Take geometries for example, we need only a floating-point radius value to represent a sphere (its center is implicitly defined as origin). This is extremely space efficient to store (resp. load) as a SDL resource, but not so much as a surface representation for displacement mapping. In the cooking phase, we may discretize the sphere into small triangles, such as an icosphere, so that it can be easily displaced according to a texture map and performing ray intersection tests on.

The last phase in the dataflow is rendering. Although it may look simple in the diagram, it is the most complex part and contains sophisticated algorithms that simulate physically based light transport upon the cooked data. The result of the simulation is a HDR image taken by a virtual camera, and is later tone-mapped to produce the final LDR output.

Data Containers

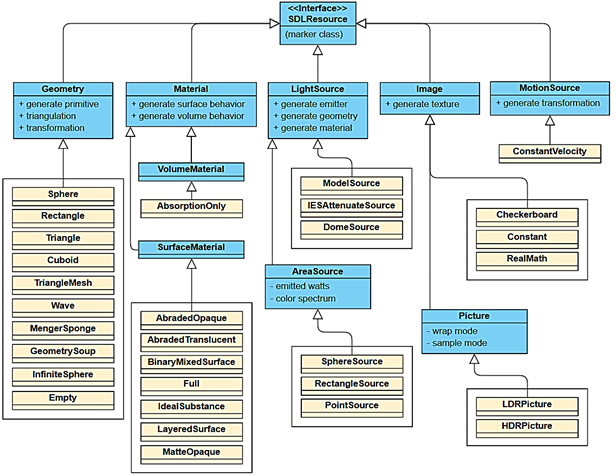

As its name suggests, each type of standalone data container represents a specific block of data and is responsible for producing cooked version of itself. They serve as the building blocks of the more complex composite data containers.

We briefly introduce some of the major container types:

- Geometry: It is like the bone of a scene: materials, lights, physical motions can attach to it like human flesh (to give them look and feel). They are basically the heart of a virtual world.

- Material: Materials are like the skin of geometries. They record surface and volume properties of a geometry, defining how a geometry will look like when light shines on them.

- Light Source: Without energy sources, you simply cannot take a picture of the scene.

- Image: Other than simple LDR, HDR pictures, images should be seen as a table that contains static data or operations in Photon4.

- Motion Source: Applying dynamic effects on geometries. If the camera in use has a finite shutter opening time, blurry images are produced due to the presence of object motion.

Composite Containers

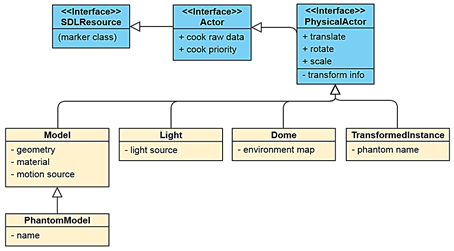

Little can be achieved if we have only standalone data containers at hand. The purpose of composite containers is to achieve aggregate behaviors on data blocks. In Photon, composite containers are often called actors since they usually contribute to the final image directly, in a sense similar to film actors. It is straightforward to see that actors are a higher level concept than standalone data containers in the class diagram that follows.

- Model Actor: Models are one of the core elements that comprise a scene. To define a model, we need a geometry, a material, and (optionally) a motion source. These data blocks, when combined, realizes a virtual object in the scene.

- Light and Dome Actor: Lights are another core element in a scene, no image can be formed without them. It takes a light source to define a light. In case of a dome, a specialized actor type is needed since lighting from the environment is special in many ways. For instance, sometimes we need a bounding box/sphere for the whole scene to properly construct a dome model large enough to encompass the scene. This made them unable to be cooked in the order just like normal light actors, they need to be cooked last.

- Phantom Actor: Photon introduces the concept of phantoms just recently. It is a generalization of data blocks that have been cooked, but not intended to be included in the scene directly. Phantoms can be accessed via their names from the cooking context (a class that encapsulates meta information of the cooking process). Phantom actor is readily applicable in case of geometry instancing, all we need is to reference the same cooked model for each instance.

We now give an overview of features implemented in Photon. For brevity, we will include only the most commonly used standalone data containers. Low level implementation details and architectures are not presented here. It is best to read Photon’s source code documentation to understand them. Below is a table showing what each type of raw data is cooked into as well as the locations of relevant source code.

What’s Next?

The above sections mainly talk about the technical aspect (design and architecture) of the renderer. I would also like to talk about the internal workings of the renderer, especially the rendering part. However, it is not my taste to have a post super long. So, see you next time!

Footnotes

-

For compiled languages, I mean C/C++, Rust, Go, Fortran, etc. Although languages like Java and Python can be compiled into bytecode, I call them interpreted languages since they require a VM to execute the code. ↩

-

A scene modeled by Frank Meinl at Crytek. ↩

-

I borrowed this name from Unreal Engine 4. In their architecture, cooking is a processing stage that makes raw data suitable for real-time use (on a selected platform). ↩

-

We also have modifier images such as

RealMathcan apply basic arithmetic operations on other images. ↩